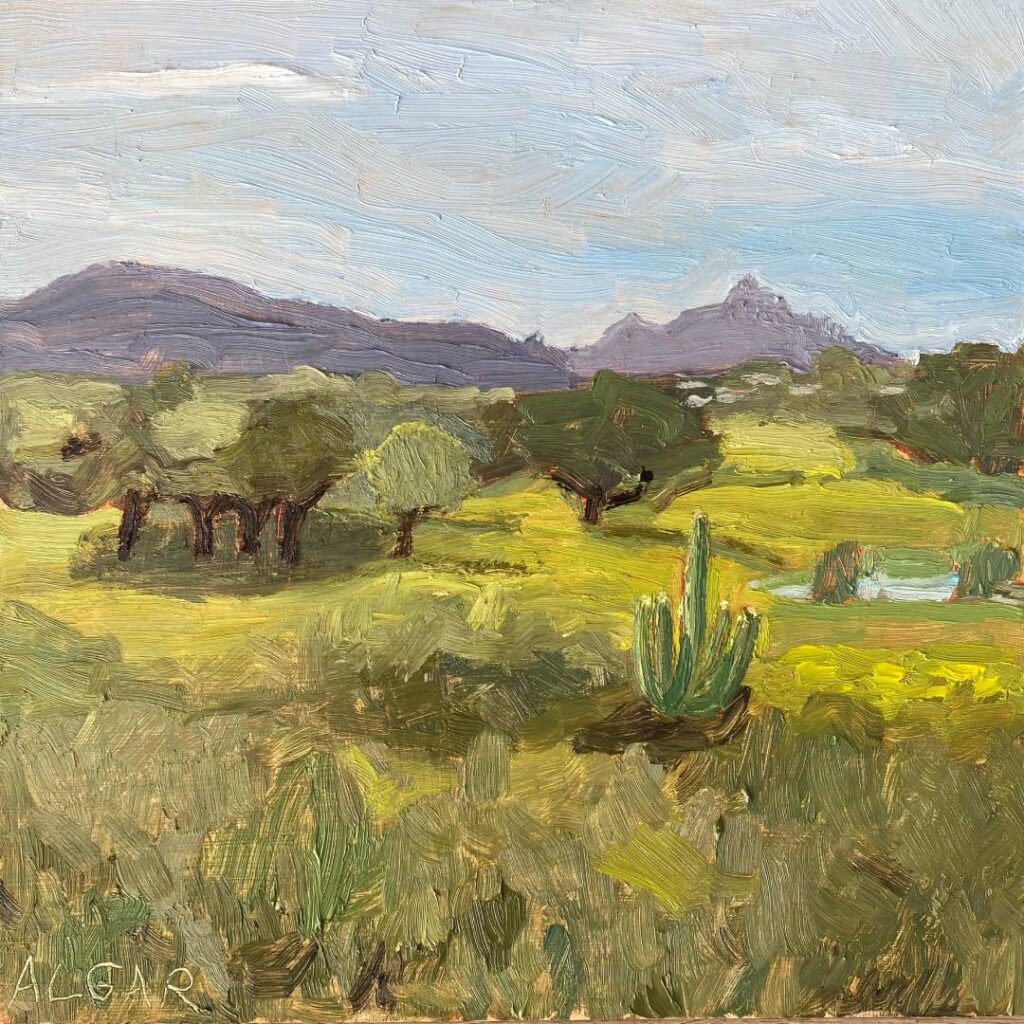

Have you ever headed out to paint, full of enthusiasm, only to find that the “perfect view” isn’t there? Maybe the weather turns, like it did one fiercely windy day when my friend Cathy and I went painting up at Stanford Hills back in the Overberg. We planned a lovely plein air session, but the Southeaster had other ideas, leaving us searching for shelter and a workable subject.

It’s a common challenge for landscape painters. We ended up at Cathy’s home on Blue Moon Farm, seeking refuge. But even there, tucked away from the wind, the “obvious” panoramic views weren’t accessible. This forced us to look differently – a skill every artist needs!

This experience was a great reminder: a compelling painting composition isn’t always about the grand vista. Sometimes, the most interesting subjects are found when you look closer or adapt to your surroundings.

So, what do you do when faced with less-than-ideal conditions or seemingly uninspiring scenery? Here are my essential tips for finding strong painting compositions, wherever you are.

Tip 1: Look Beyond the ‘Grand View’ – Focus on Elements

Instead of searching only for the big, obvious landscape, train your eye to see smaller vignettes and design elements:

- Zoom In: What happens if you focus on just one or two interesting shadow shapes or highlights? Can you build a composition around the interplay of light and dark?

- Look For Interesting Light Patterns: Look for how sunlight falls across objects, creating intriguing shapes and contrasts. Dappled light through trees, long shadows, or reflected light can all be starting points.

- Find Big, Pleasing Shapes: Squint your eyes. What are the dominant shapes you see? Look for how large masses (trees, buildings, hills, clouds) connect and interact to form a pleasing abstract design. Don’t underestimate the power of simple, strong shapes.

Tip 2: Identify a Clear Focal Point

Even in a complex scene, having a clear focal point helps guide the viewer’s eye and anchors your painting.

- What Grabs Your Attention? Look for something specific – a distinctive tree, a brightly coloured building, a gate, a unique shadow.

- Build Around It: Once you have a potential focal point, arrange the other elements in your composition to support and lead the eye towards it. On that windy day, I chose a small white building as my focal point, using a reddish tree, distant mountains, and even a subtle cell tower to add depth and interest around it.

Tip 3: Use the Rule of Thirds (Wisely!)

This classic guideline is excellent for creating balanced and dynamic compositions.

- Imagine a Grid: Mentally (or physically using your phone camera grid or viewfinder) divide your canvas or scene into nine equal sections with two horizontal and two vertical lines.

- Place Key Elements: Position your focal point or other important elements along these lines or, ideally, where the lines intersect.

- Avoid the Centre: Generally, placing your main subject smack in the middle can feel static. The rule of thirds encourages a more engaging visual flow. Remember, it’s a guideline, not an unbreakable law!

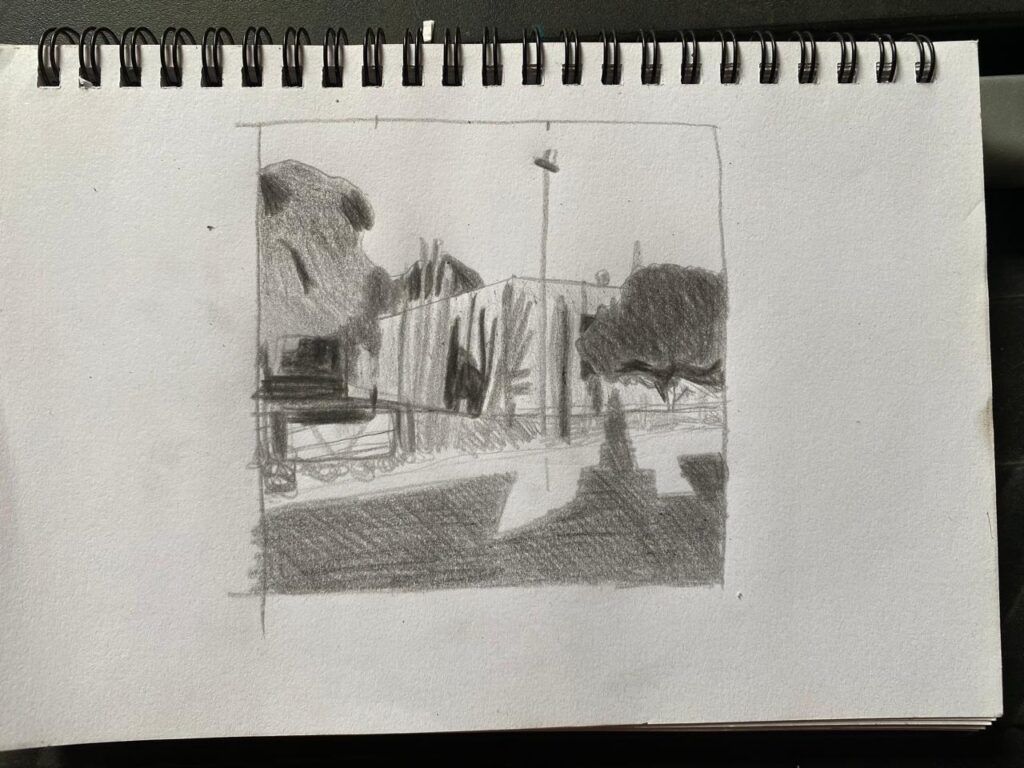

Tip 4: Test Ideas with Thumbnail Sketches (Notan)

Before committing to your canvas, explore options quickly in your sketchbook. Small, simple sketches are invaluable.

- Notan Thumbnails: A ‘Notan’ is a Japanese design concept focusing on the balance of light and dark shapes. Try creating tiny (thumbnail-sized) sketches using just black and white (or dark and light) to see if the basic abstract design of your potential composition is strong and pleasing.

- Experiment: Try cropping the scene differently, shifting the focal point, or changing the orientation (portrait vs. landscape) in these quick sketches.

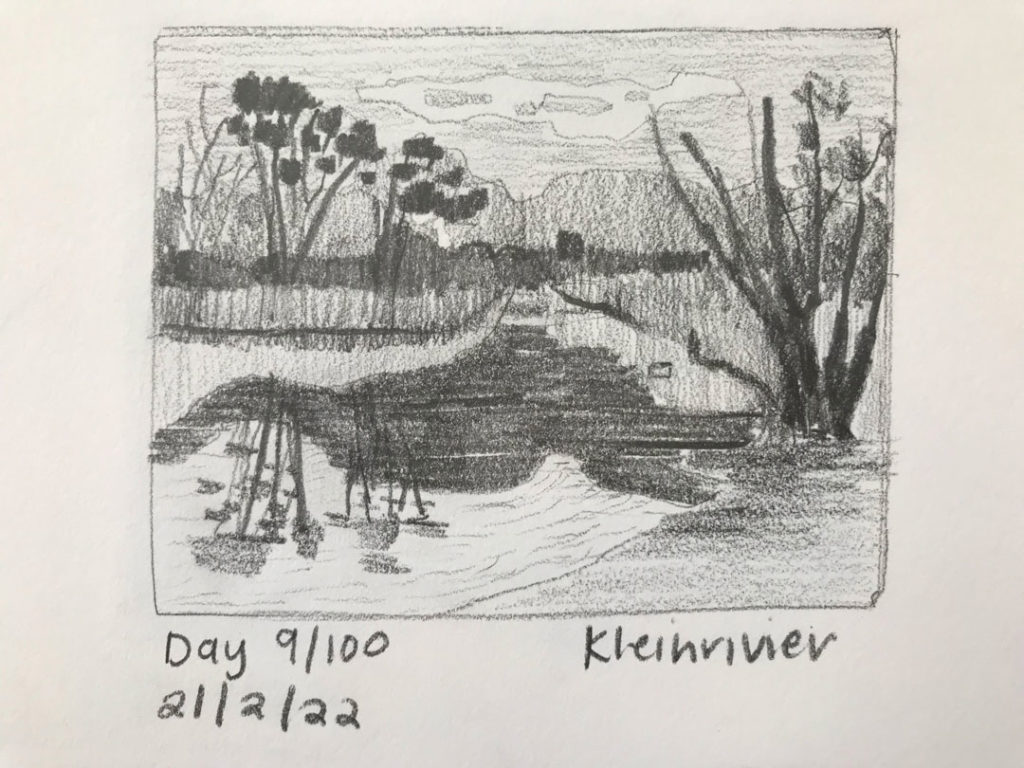

Tip 5: Plan Your Values Before You Paint

Once you’ve settled on a composition, take 10-15 minutes to create a value study. This map of lights and darks is crucial for a successful painting.

- Simplify to 3-5 Values: Don’t get caught up in details yet. Identify the main areas of dark, medium, and light value in your composition.

- Recommended Tool: A 4B pencil (shaved to a chisel point with a craft knife) is great for this. You can create thin lines and broad areas of tone easily.

- Map it Out: Lightly sketch your main shapes. Then, shade in your darkest darks (press harder), your mid-tones (press lightly), leaving the white of the paper as your lightest value.

Planning the composition and values in my sketchbook before starting the painting.

Conclusion: Composition is Key

Finding a great subject to paint isn’t just about luck or stumbling upon a perfect postcard view. It’s about learning to see compositional possibilities everywhere – even on a windy day behind some succulents! By looking for strong shapes, identifying focal points, using guidelines like the rule of thirds, and planning with value studies, you can create compelling paintings from almost any scene.